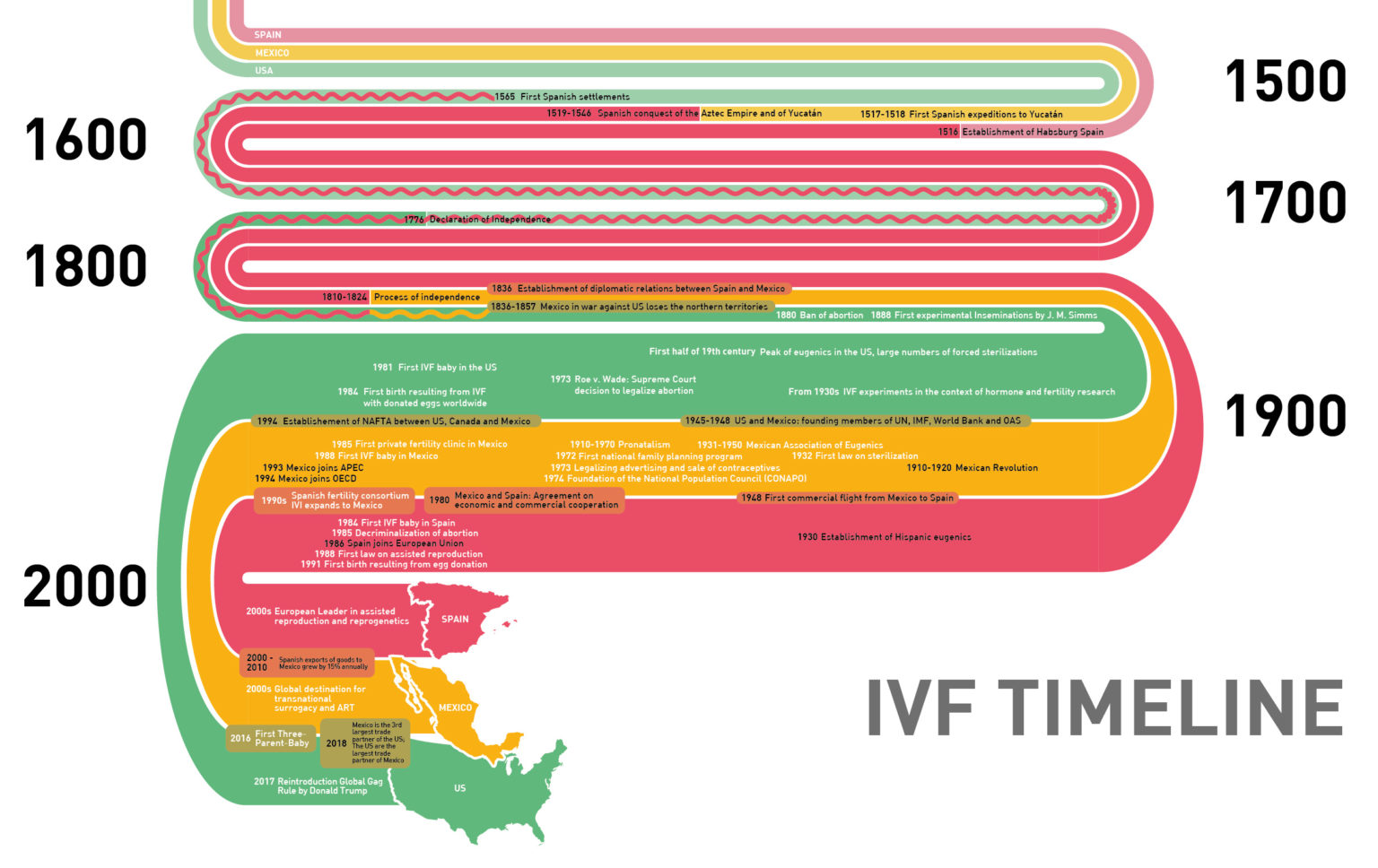

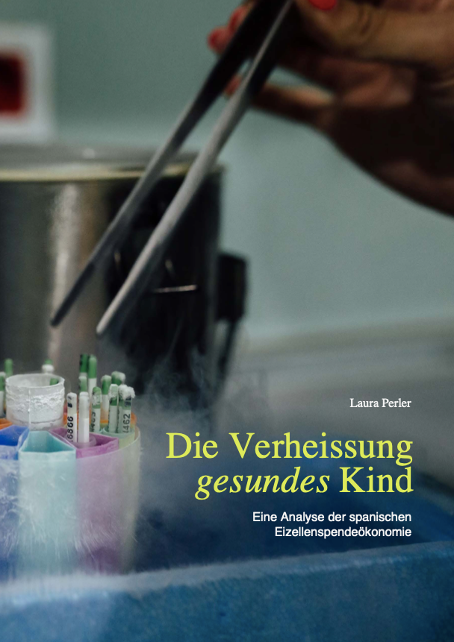

Spain is the European leader in reproductive medicine. A liberal legislation and a large number of private reproductive clinics attract a steadily growing number of international patients who travel to Spain to fulfill their dream of having a family. Two techniques are crucial for this transnational mobility: egg donation and reprogenetics. In my work, I study the interdependencies of these two techniques by analysing the use of the genetic carrier test in egg donation cycles. The interplay of those techniques is due to the main goal of reproductive medicine, which is to produce ‘healthy’ children.

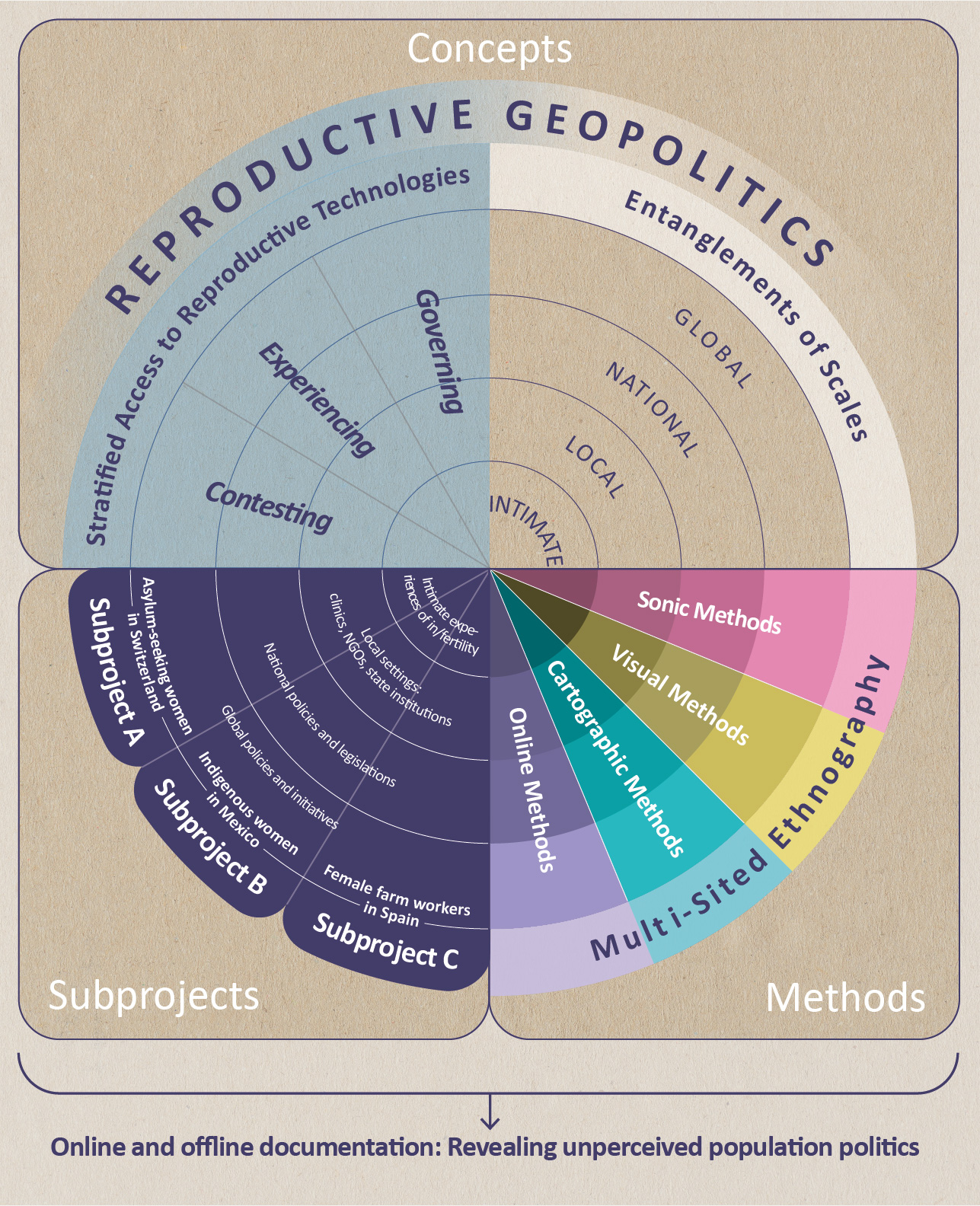

I situate my work within a (transdisciplinary) feminist Science & Technology Studies (STS) debate that analyses new forms of appropriation of women’s bodies in a global bioeconomy. While research has already analysed egg donation in relation to classist and racist structures, little is known about the prob- lematics of genetic diagnostic techniques in the context of egg donation. My work starts addressing this gap. Following a praxeographic approach, I explore how the imaginary of a ‘healthy’ child manifest itself in the form of multiple practices in the clinic’s everyday life. I also discuss how this affects different actors differentely (egg donors, egg recipients, clinic staff, geneticists). Inspired by the approaches of a ‘sensory ethnography’, I aim to make this universe of Spanish reproductive medicine not only cognitively comprehensible but also sensually tangible through written, visual and auditive elements, which are accessible through hyperlinks.

The ‘healthy’ child, this is my main thesis, is an important social imaginary in the contemporary Spanish reproductive clinic. The social imaginary is the conceptual prism through which I make visible the multiple entanglements of power relations, collective imaginaries of the future and contemporary practices in the clinic. In doing so, I show that the ‘healthy’ child is based on ideal, material and bodily relations of inequality, through which the egg donor is (re)produced as a subaltern subject. The collective visions of the future in the clinic point to the fact that the use of (genetic) selection techniques is normalised via a narrative of progress. Finally, the analysis of the use of the genetic carrier test shows how the imaginary materialises in practices that (re)produce the underlying power relations of a transnational bioeconomy. This reification of an abstract imaginary in social practices and medical techniques is not a linear process, but is characterised by multiple contradictions and ambivalences. In my work, I show that it is precisely the fragility and volatility of knowledge structures in relation to the genetic carrier test that result in a stable basis for the imaginary of the ‘healthy’ child. The work thus shows that assisted reproduction is already today a genuinely selective reproduction. The ‘healthy’ child is not only a dream, but (re)produces socio-economic as well as ideational-normative structures of inequality.