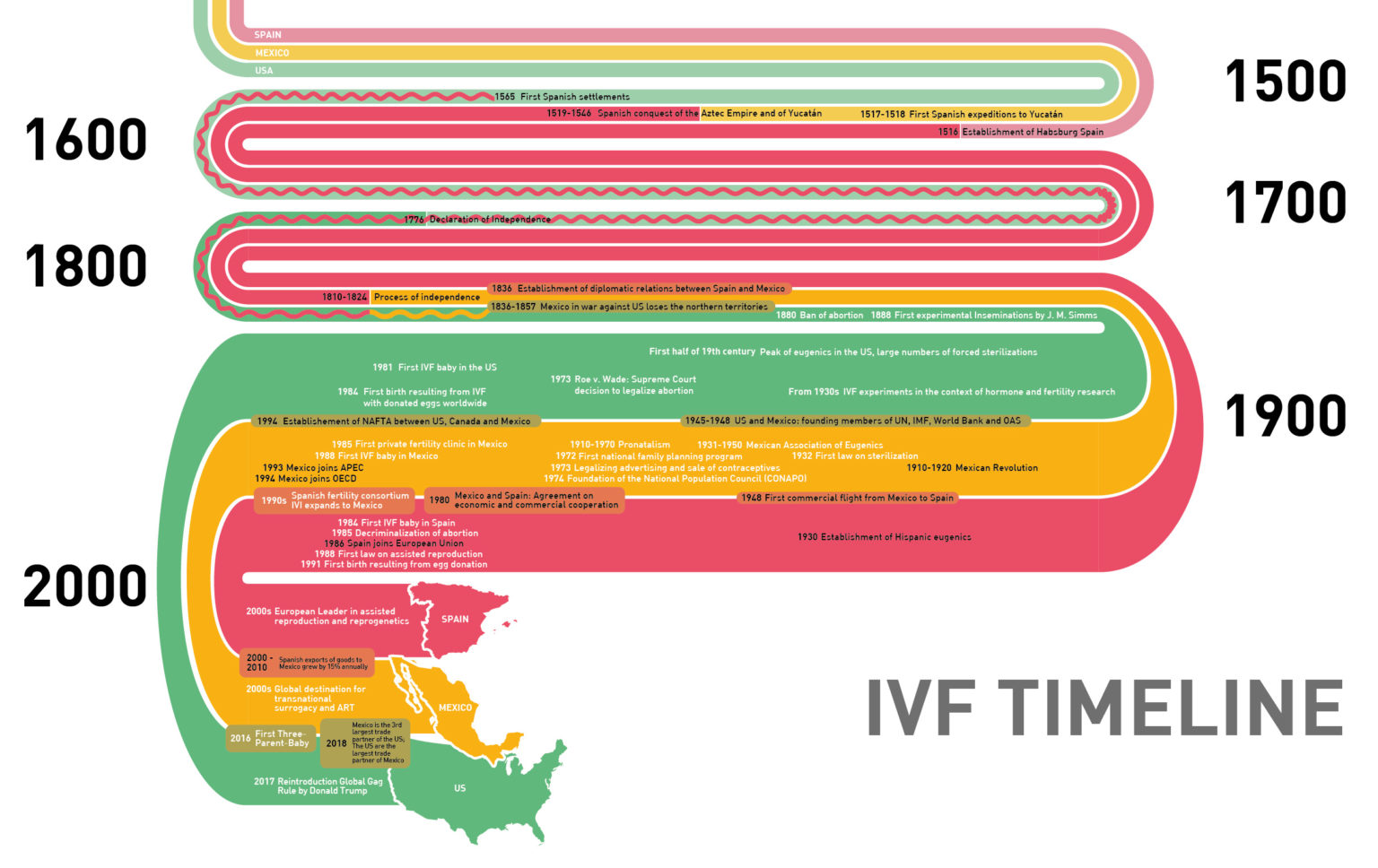

Illustration by Luis Armando Zacarias, 2023

In Mexico, birth control policies have been the site of gender, race, class, and colonial relationships. Before 1973, the Mexican government stated, “To govern is to populate.” This slogan was associated at the same time with racial and national ideas. To populate was a synonym for educating, moralizing, improving the race, civilizing, and affirming the nation’s freedom (Camarillo Quesada 2022). Birth rates were encouraged to promote the population’s growth; contraception and abortion were prohibited. However, the United Nations International Conference on Population and Development (ICPD), held in Cairo in 1994, represented a “conceptual break” (Brugeilles 2004). It changed the national and international approach to birth control policies.

Sexual and reproductive rights discourse became dominant, but the ‘gender-friendly’ agendas were highly problematic. For instance, in Peru, the rhetoric of reproductive health and women’s empowerment became the platform for sterilizing thousands of women without their consent (Chaparro-Buitrago 2021). The Mexican government launched a Malthusian demographic policy to control population growth. Policies were based on the efficiency and effectiveness of the means and, more specifically, on “goals” to be achieved. Goals of how many women should take contraception or be sterilized were established, and health professionals were in charge of achieving them. Aggressive sterilization campaigns, forced or coerced contraception, and intrusive family planning programs were current practices. The primary targets were low-income, rural, peasant, and indigenous women. There is, however, a lack of systematic collection of information on sterilization cases, specifically among indigenous communities. Yet, even today, sterilizations among indigenous women are significantly higher than among non-indigenous women (Castro 2021). And in 2008, the Encuesta de Salud y Derechos de las Mujeres Indígenas (Instituto Nacional de Salud Pública 2008) concluded that almost one-third of indigenous women of reproductive age were sterilized at the moment of the survey.

Presently, gendered and racialized forms of definitive contraception are a no-topic and seem “part of the past.” On the one hand, there is steady documentation of cases of (forced) sterilization by human rights organizations, the press, and national health institutions (i.e., Comisión Nacional de Arbitraje Médico). On the other hand, except for some cases (Cosío Zavala 1994; Freyermuth Enciso 2001; Menéndez 2009; Castro 2021; Gaussens 2020), national and international literature on social sciences have shown little interest in the experiences of women targeted by the above-mentioned family planning policies. Likewise, little is known about the continuities between the (old) family planning policies and contemporary forms of population control (Bhatia et al. 2020).

This research project is devoted to exploring the experiences of sterilization (tubal ligation and hysterectomy) of low-income, rural, peasant, and indigenous Mexican women as part of national family planning and global birth control policies in developing countries. Women’s experiences are entangled with reproductive and racial policies and the effects of population control on women’s intimate lives and the making of the national body. Likewise, the voices of health professionals performing sterilizations provide a privileged perspective to analyze the strategies to set up such policies. Ethnographic (in situ observation, informal conversation), qualitative (in-depth interviews and collective interviews), as well as affectual methodologies (e.g., body mapping) will be used to understand Mexico’s reproductive (geo)politics and their effects on women’s lives. So far, exploratory fieldwork has shown that “campaigns of sterilization” in state-subsidized hospitals still exist. Moreover, in-depth interviews with low-income women suggest that the dichotomy of wanted/unwanted, voluntarily/forced sterilizations might not comprehensively explain the complexity of their experiences.

Bhatia, Rajani, Jade S. Sasser, Diana Ojeda, Anne Hendrixson, Sarojini Nadimpally, and Ellen E. Foley. 2020. “A Feminist Exploration of ‘Populationism’: Engaging Contemporary Forms of Population Control.” Gender, Place & Culture 27 (3): 333–50. https://doi.org/10.1080/0966369X.2018.1553859.

Brugeilles, Carole. 2004. “La Politique de Population Au Mexique.” In Les Politiques de Planification Familiale. Cinq Expériences Nationales, edited by Arlette Gautier, 115–63. Paris: Laboratoire Population, Environnement, Développement/Université Paris Nanterre.

Camarillo Quesada, Julio Andrés. 2022. “Peupler et Coordonner. Une Ontologie Du Présent à La Lumière de l’histoire de l’anthropologie Appliquée Au Mexique.” Paris: Université de Paris.

Castro, Roberto. 2021. “Hacia Una Sociología de La Anticoncepción Forzada En México.” In Género y Sexualidad En Disputa : Desigualdades En El Derecho a Decidir Sobre El Propio Cuerpo Desde El Campo Médico, edited by Karina Bárcenas Barajas, 37–64. Mexico City: IIS/UNAM.

Chaparro-Buitrago, Julieta. 2021. “The Promise of Empowerment: Reproductive Justice, Decolonial Feminisms, and the Cases of Forced Sterilziation in Peru.” Massachusetts: University of Massachusetts Amherst.

Cosío Zavala, María Eugenia. 1994. Changements de Fécondité Au Mexique et Politiques de Population. Paris: Editions L’Harmattan/IHEAL.

Freyermuth Enciso, Graciela. 2001. “The Background to Acteal: Maternal Mortality and Birth Control, Silent Genocide?” In The Other Word: Women and Violence in Chiapas Before and After Acteal, edited by Rosalva Aída Hernández Castillo, 57–73. Santa Cruz de la Sierra: International Work Group for Indigenous Affairs.

Instituto Nacional de Salud Pública. 2008. “Encuesta de Salud y Derechos de Las Mujeres Indígenas. ENSADEMI 2008.” Cuernavaca: Instituto Nacional de Salud Pública.

Menéndez, Eduardo L. 2009. “De Racismos, Esterilizaciones y Algunos Otros Olvidos de La Antropología y La Epidemiología Mexicanas.” Salud Colectiva 5 (2): 155. https://doi.org/10.18294/sc.2009.258.